Discover the enchanting world of antique maps & vintage prints.

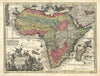

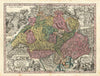

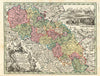

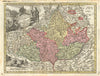

We are dealers in rare, antique & authentic maps and prints of all parts of the world, published from the 16th to the 20th centuries. We only sell authentic, original items - a Certificate of Authenticity comes with every order. We are based in London and offer fast worldwide shipping

Shop the Largest

Range of Authentic Antique Maps & Prints online.

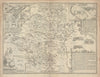

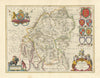

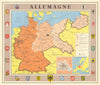

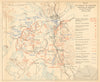

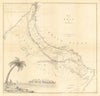

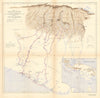

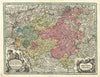

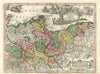

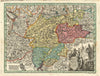

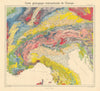

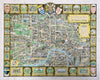

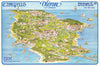

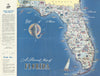

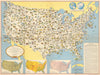

Our catalogue of over 80,000 items spans everything from rare discoveries to affordable gems. Explore nautical and astronomical charts, city plans, military, fantasy, pictorial, and wine maps — plus topographical views and animals, bird and botanical prints. We’re particularly strong in maps of London, British Isles counties, US states, French departments, and Vanity Fair "Spy" cartoons.

Shop Recent Highlights

Maps are endlessly fascinating - in their unexpected details, and the way they illuminate moments in history.

Maps are endlessly fascinating - in their unexpected details, and the way they illuminate moments in history.

A Family Business - Antiquarian Map Dealers for 50 years.

I’m Richard, an antique map dealer like my father before me. For me, it’s never felt like work — each day brings the thrill of travelling vicariously through place and time. I’m passionate about unearthing the unusual, eclectic and long-forgotten so we can offer you the largest selections anywhere — from rare discoveries to affordable gems. We're proud to supply collectors, museums, archives, interior designers, gift seekers, and fellow dealers alike

Spy Cartoons

Bird & Animal Prints

Nautical Charts

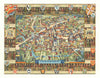

City plans

Wine maps

Star Charts

Münster’s Cosmographia

A landmark 16th-century work combining Renaissance discoveries and classical geography, richly illustrated with woodcut maps, city views, portraits, and ethnographic scenes. Including some of the earliest separate maps of the Americas, it helped shape European views of the world during the Age of Discovery.

Oxford’s "Dreaming Spires” by Rudolph Ackermann

Finely hand-coloured aquatint plates by Rudolph Ackermann of Oxford's colleges, chapels, and public buildings, alongside vivid scenes of academic life and ceremonial traditions (1814)

London Maps & Views

Harry Beck's Underground maps, Parish maps, City of London Ward plans, 18th century views of vanished buildings or vintage maps of your neighbourhood - We've got them all

Great Britain's Coasting PIlot

First published in 1693, Greenvile Collins’ sea charts—part of the first systematic sea atlas of the coastal waters of the British Isles—are a foundational work in British maritime cartography. Commissioned by the diarist Samuel Pepys, then Secretary to the Admiralty, these charts are both historically significant and visually striking.

Ordnance Survey 5ft Plan of York

Find your house in these extraordinarily detailed plans of mid-19th century York. A beautifully hand-coloured snapshot of the city just before the large-scale industrial transformation of the Victorian era

Maps are endlessly fascinating - in their unexpected details, and the way they illuminate moments in history.

A map or print can celebrate your roots or evoke a cherished memory. Whether for yourself or as a gift, we're sure you'll find something to treasure.

Any questions? Get in touch – We’re here to help!

Need help finding something special or want to know more? We're here to assist — whether you're looking for advice on collecting, caring for, or investing in antique maps and prints. Want to see before you buy? Contact us to arrange a viewing — we regularly welcome both curious locals and overseas visitors. Have something to sell? We buy books, maps, and atlases

![Midle-sex [with] London & Westminster. John Speed county map. Overton 1710](http://www.antiquemapsandprints.com/cdn/shop/files/P-8-005948a_800933ce-152f-4b02-888c-2860759716b4.jpg?v=1753354614&width=165)

![Midle-sex [with] London & Westminster. John Speed county map. Overton 1710](http://www.antiquemapsandprints.com/cdn/shop/files/P-8-005948a_800933ce-152f-4b02-888c-2860759716b4_100x100.jpg?v=1753354614)

![Midle-sex [with] London & Westminster. Speed county map. Bassett & Chiswell 1676](http://www.antiquemapsandprints.com/cdn/shop/files/P-8-005947a_d6835bdb-bc05-4eb7-9635-a2fe3da32def.jpg?v=1753354614&width=165)

![Midle-sex [with] London & Westminster. Speed county map. Bassett & Chiswell 1676](http://www.antiquemapsandprints.com/cdn/shop/files/P-8-005947a_d6835bdb-bc05-4eb7-9635-a2fe3da32def_100x100.jpg?v=1753354614)